Neuropsychiatric Reactions to Finasteride: Nocebo or True Effect?

Received: 02-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. jbclinphar-23-85201; Editor assigned: 04-Jan-2023, Pre QC No. jbclinphar-23-85201; Reviewed: 19-Jan-2023 QC No. jbclinphar-23-85201; Revised: 26-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. jbclinphar-23-85201; Published: 02-Feb-2023

Citation: Brezis M. Neuropsychiatric Reactions to Finasteride: Nocebo or True Effect? J Basic Clin Pharma. 2023;14(1):220-222.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@jbclinpharm.org

Abstract

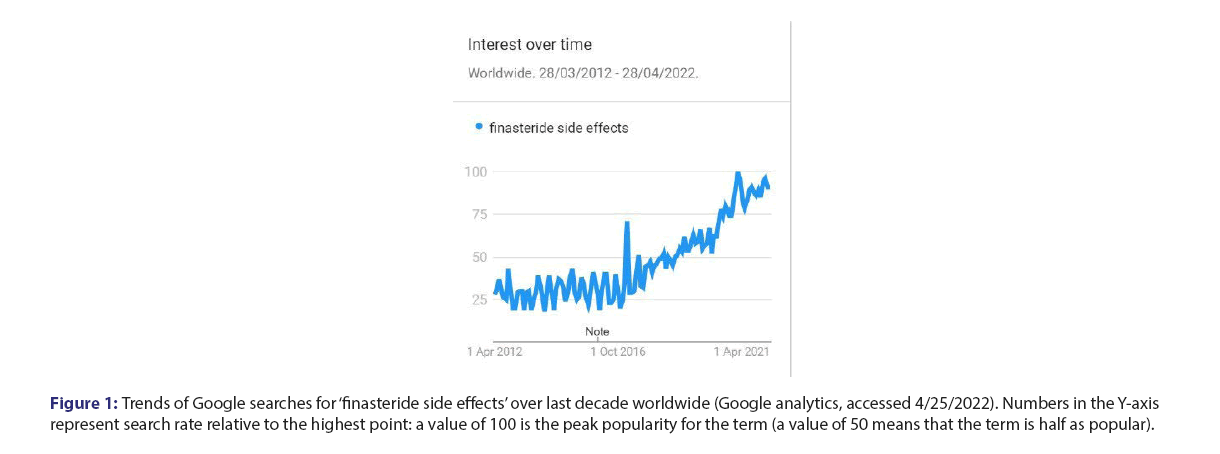

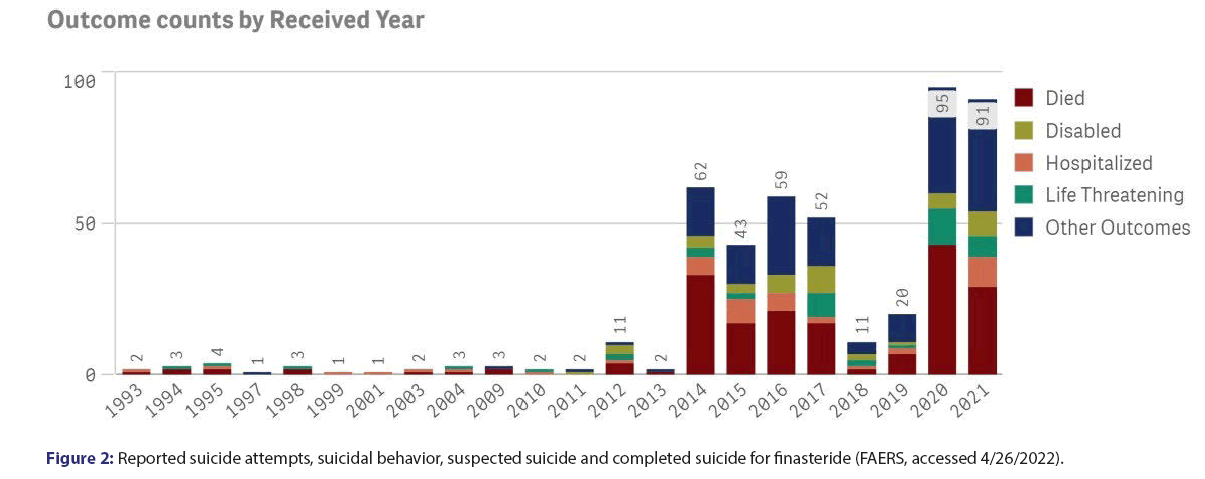

Finasteride, which inhibits conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, is in wide use for hair loss and prostatic hyperplasia. Reports of adverse reactions increasingly suggest that finasteride may cause depression, anxiety, suicidality and sexual dysfunction, even after discontinuation of the drug. On the other hand, some publications have claimed that this could represent simulated reporting of a nocebo effect. In the present paper, we analyse reports to the FDA of neuropsychiatric events for finasteride in comparison to control medications, and demonstrate remarkably disproportionate safety signals for finasteride. Furthermore, the rise in neuropsychiatric reactions to finasteride over the last decade concurs with a striking increase in suicides reported to the FDA in relationship to this medication. In addition, Google analytics show a growing interest for finasteride in recent years, including concern about side effects. Since suicide has not been associated with a nocebo effect, it seems likely that we are facing real and serious adverse effects on mood from finasteride. Increased reporting could relate to enhanced awareness and not to a nocebo effect. Health care professionals should be aware of these concerns and share them with patients to allow informed decision regarding their care.

https://transplanthair.istanbul

https://hairclinicturkey.co

https://hairclinicistanbul.co

https://besthairtransplant.co

https://hairtransplantistanbul.co

Keywords

Finasteride, Adverse effect, Suicide, Anxiety, Mood, Neurosteroids, Neuropsychiatric reaction

Description

Finasteride, an inhibitor of the 5α-reductase-catalysed conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, is in wide use for hair loss and prostatic hyperplasia. Increasingly reports of neuropsychiatric adverse reactions suggest that finasteride may cause depression, anxiety, suicidality and sexual dysfunction, which sometimes persist after discontinuation of the drug. On the other hand, some scholars have claimed that this represents simulated reporting of a nocebo effect. In the present paper, we analyse reports to the FDA of neuropsychiatric events for finasteride in comparison to control medications, and demonstrate strikingly disproportionate safety signals for finasteride. We have analysed neuropsychiatric events reported to the FDA for finasteride in comparison to other medications. The numbers in the upper rows are reactions reported to FAERS (accessed in 3/8/2020). The last two rows are data available for year 2019 in the USA at https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Default.aspx. Both minoxidil and spironolactone are used for alopecia, and Inderal has been linked to depression. The relative risk for adverse reactions to finasteride in comparison to Spironolactone (S) and to Inderal (I) was adjusted for the corresponding relative rate of prescriptions or patients (the relative risk in comparison to minoxidil was not adjusted as prescriptions data were not available). The right columns in the table show markedly increased risks of depression and anxiety-in the range of 14-33 times higher-for finasteride than for controls. The analysis also shows increased risks of insomnia, fatigue, suicidality and suicide-in the range of 2-14 times higher-for finasteride than for controls. Disproportionate safety signals for finasteride concur with reports by others [1-6]. Some publications have suggested this may represent simulated reporting of a nocebo effect. An impact of media coverage, through cognitive availability bias, is usually transient, and negative news about finasteride have in fact decreased (from 3.5 items per month in the years 2011-2, to 1.0 per month in recent years-LexisNexis database, accessed 4.25.2022) [7-9]. Alternatively, awareness may be increased by discourse in social media, as reflected by an analysis of web searches related to finasteride: Google analytics for trends show growing interest for finasteride in recent years, including concern about side effects (Figure 1). Users of finasteride could either imagine or realize that symptoms such as sexual dysfunction, fatigue and altered mood relate to a cosmetic medication they have been taking. A rise in reporting to the FDA of neuropsychiatric reactions over the last decade concurs with a remarkable increase in suicides related to finasteride (Figure 2). Reports to the FDA of neuropsychiatric events for finasteride in comparison to control medications demonstrate remarkably disproportionate safety signals for finasteride with a striking increase in suicides. Google analytics show a growing interest for finasteride in recent years with enhanced awareness of its side effects. Since suicide has not been associated with the nocebo effect, more likely is a true effect on mood from finasteride, via inhibition of the 5-alpha reductase enzyme needed in the biosynthesis of neurosteroids-as shown in animals and patients studies [10-15]. Mitigation of finasteride-related suicidality by concomitant administration of testosterone4 is also consistent with an actual biological effect. A potential key role of brain hormones in the control of mood is evidenced by novel neurosteroid-based antidepressant agents, recently approved by the FDA [16]. Awareness of drug safety issues can be slowly arising, as side effects are under-reported by physicians and by pharmaceutical companies [17,18]. Earlier and more direct reporting by patients for safety monitoring, as increasingly done in pharmacovigilance may accelerate the detection of drug safety signals-in a paradigm shift already widely implemented in healthcare practice [19-21]. A recent update on the management of hair loss omitted to mention depression and suicidality-debilitating and potentially fatal risks from finasteride, which may continue after its discontinuation [22]. Two large pharmacovigilance studies have shown a significant risk for depression and suicidality with finasteride, confirming previous reports of serious psychological adverse effects, including anxiety, insomnia, fatigue, depressed mood and completed suicide [1,2,23]. Laboratory research shows that finasteride reduces levels of neurosteroids modulating mood and induces in rats long term effects on depressive-like behavior, hippocampal neurogenesis and inflammation [13,23]. The cosmetic effect of finasteride on self-image may improve mood and quality of life. Such improvements for a bulk of people in post marketing surveillance can dilute or even completely mask a drastic deterioration of mood in a significant minority of patients. Competing effects, including both benefit and harm from a medication, might explain conflicting data in the literature and the heterogeneity found in systematic reviews on the risk of depression for finasteride, as for isotretinoin [24,25]. When considering finasteride to improve self-image and quality of life, it seems critical to warn individual patients about the potential risk of getting just the opposite outcome with neuropsychiatric reactions associated with a dismal, potentially permanent deterioration in quality of life. Health care professionals should be aware of these concerns, share them with patients and discuss alternative options, to allow a truly informed decision regarding their care.

| Reaction | Finasteride | Minoxidil | Spironolactone | Inderal | Adjusted Relative Risk for Finasteride | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. (S) | vs. (I) | |||||

| Depression | 2040 | 134 | 124 | 153 | x21 | x14 |

| Anxiety | 1643 | 143 | 85 | 51 | x25 | x33 |

| Insomnia | 822 | 20 | 163 | 99 | x6 | x9 |

| Fatigue | 799 | 118 | 481 | 75 | x2 | x11 |

| Suicidality | 550 | 22 | 101 | 41 | x7 | x14 |

| Suicide | 119 | 12 | 91 | 51 | x2 | x2 |

| Number of prescriptions | 89,86,897 | 0 | 1,14,32,027 | 92,77,061 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of patients | 23,14,978 | 0 | 29,85,578 | 24,21,089 | 0 | 0 |

Table: Neuropsychiatric reactions reported to the FDA for finasteride in comparison to similar reactions reported for other medications

Figure 1: Trends of Google searches for ‘finasteride side effects’ over last decade worldwide (Google analytics, accessed 4/25/2022). Numbers in the Y-axis represent search rate relative to the highest point: a value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term (a value of 50 means that the term is half as popular).

Conclusion

Reports to the FDA of neuropsychiatric events for finasteride in comparison to control medications show disproportionate safety signals for finasteride with a striking increase in suicides. Increased reporting could relate to enhanced awareness and not to a nocebo effect. In pharmacovigilance surveys, the actual rate of serious adverse effects on mood from finasteride in some patients may be diluted by the benedficial cosmetic outcome in many others. Health care professionals should be aware of these concerns and share them with patients to allow informed decision regarding their care.

References

- Welk B, McArthur E, Ordon M, et al. Association of suicidality and depression with 5α-reductase inhibitors. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):683-691.

- Nguyen DD, Marchese M, Cone EB, et al. Investigation of suicidality and psychological adverse events in patients treated with finasteride. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(1):35-42.

- Pompili M, Magistri C, Maddalena S, et al. Risk of depression associated with finasteride treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021;41(3):304-309.

- Campbell K, Velazquez O, Sullivan J, et al. Finasteride-Associated Suicide and Depression in Men Treated for Hypogonadism and Impotence. J Sex Med. 2022;19(4):S4-5.

- Argibay GM, Hiyoshi A, Fall K, et al. Association of 5α-reductase inhibitors with dementia, depression, and suicide. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(12):e2248135.

- Nguyen DD, Herzog P, Cone EB, et al. Disproportional signal of sexual dysfunction reports associated with finasteride use in young men with androgenetic alopecia: A pharmacovigilance analysis of VigiBase. J Am Acad Dermatol.

- Brezis M, Reichert HD, Schwaber MJ. Mass Media-Induced Availability Bias in the Clinical Suspicion of West Nile Fever. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(3):234-235.

- Taylor D, Stewart S, Connolly A. Antidepressant withdrawal symptoms-telephone calls to a national medication helpline. J Affect Disord.2006;95(1-3):129-133.

- MacKrill K, Gamble GD, Bean DJ, et al. Evidence of a media-induced nocebo response following a nationwide antidepressant drug switch. CPE.2019;1(1):1-2.

- Colloca L, Barsky AJ. Placebo and nocebo effects. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):554-561.

- Melcangi RC, Santi D, Spezzano R, et al. Neuroactive steroid levels and psychiatric and andrological features in post-finasteride patients. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;171:229-235.

- Li L, Kang YX, Ji XM, et al. Finasteride inhibited brain dopaminergic system and open‐ field behaviors in adolescent male rats. CNS Neurosci Ther.2018;24:115-125.

- Diviccaro S, Giatti S, Borgo F, et al. Treatment of male rats with finasteride, an inhibitor of 5alpha-reductase enzyme, induces long-lasting effects on depressive-like behavior, hippocampal neurogenesis, neuroinflammation and gut microbiota composition. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;99:206-215.

- Godar SC, Cadeddu R, Floris G, et al. The steroidogenesis inhibitor finasteride reduces the response to both stressful and rewarding stimuli. Biomolecules. 2019;9(11):749.

- Sasibhushana RB, Rao BS, Srikumar BN. Repeated finasteride administration induces depression-like behavior in adult male rats. Behav Brain Res. 2019;365:185-9.

- Gunay A, Pinna G. The novel rapid-acting neurosteroid-based antidepressant generation. Current Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. 2022;24:100340.

- Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):865-9.

- Golder S, Loke YK, Wright K, et al. Reporting of adverse events in published and unpublished studies of health care interventions: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2016;13(9):e1002127.

- Bahri P, Pariente A. Systematising Pharmacovigilance Engagement of Patients, Healthcare Professionals and Regulators: A Practical Decision Guide Derived from the International Risk Governance Framework for Engagement Events and Discourse. Drug Saf. 2021;44(11):1193-208.

- Inácio P, Cavaco A, Airaksinen M. The value of patient reporting to the pharmacovigilance system: A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(2):227-46.

- Nelson EC, Eftimovska E, Lind C, et al. Patient reported outcome measures in practice. BRIT MED J. 2015;350.

- Mirmirani P, Fu J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Nonscarring Hair Loss in Primary Care in 2021. JAMA. 2021;325(9):878-9.

- Irwig MS. Finasteride and suicide: a postmarketing case series. Derm. 2020;236(6):540-5.

- Baldessarini RJ, Pompili M. Further Studies of Effects of Finasteride on Mood and Suicidal Risk. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021;41(6):687-8.

- Li C, Chen J, Wang W, et al. Use of isotretinoin and risk of depression in patients with acne: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2019;9(1):e021549.