Drug utilization in pediatric neurology outpatient department: A prospective study at a tertiary care teaching hospital

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Supriya D. Malhotra

Department of Pharmacology, Smt. NHL Municipal Medical College, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India.

E-mail: supriyadmalhotra@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Neurological disorders are a significant cause of morbidity, mortality and adversely affect quality of life among pediatric patients. In India, more than 30% population is under 20 years of age, many of whom present late during the course of illness. Several drugs prescribed to pediatric population suffering from neurological disorders may be off label or unlicensed. Aims and Objectives: To study drug use pattern, identify off‑label/unlicensed drug use and to check potential for drug‑drug interactions in patients attending outpatient department of pediatric neurology at a tertiary care teaching hospital. Methodology: Prescriptions of patients attending pediatric neurology outpatient department were collected prospectively for 8 weeks. They were analyzed for prescribing pattern, WHO core prescribing indicators, off‑label/unlicensed drug use and potential for drug‑drug interactions. Result: A total of 140 prescriptions were collected, male female ratio being 2:1. Epilepsy was the most common diagnosis (73.57%) followed by breath holding spells, migraine and developmental disorders. Partial seizure was the most common type of epilepsy (52.42%). Average number of drugs prescribed per patient was 1.56. Most commonly prescribed drug was sodium valproate (25.11%) followed by phenytoin (11.41%). About 16% of the prescriptions contained newer antiepileptic drugs. More than 60% of the drugs were prescribed from WHO essential drug list. In 8.57% of cases drugs were prescribed in off‑label/unlicensed manner. Twenty‑six percent prescriptions showed potential for drug interactions. Conclusion: Epilepsy is the most common neurological disease among children and adolescents. Sodium valproate is the most commonly prescribed drug. A few prescriptions contained off‑label/unlicensed drugs.

Key words

Antiepileptic drug, breath holding spells, drug utilization, epilepsy, pediatric neurology, potential drug-drug interactions

Introduction

Neurological disorders are a major cause of morbidity, mortality, disability, and adversely affect the quality of life among pediatric age group.[1] Major neurological disorders among children include epilepsy, headache, migraine, cerebral palsy, behavior related disorders - attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD), breath holding spells (BHSs), autism and related pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs), developmental delay, and neurodegenerative diseases, etc.[2] Epilepsy is the most common neurological disorder among pediatric age group. Prevalence of seizure is about 10% among pediatric age group.[2] Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are the mainstay of managing epilepsy. For children with epilepsy, the prognosis is generally good, but 10-20% has persistent seizure refractoriness to drugs, and such cases are diagnostic and management challenge.[2] The desired outcome of AED therapy is for patients to be seizure-free throughout the rest of their lives, and it depends on many factors such as identification of underlying cause, type of seizure and selection of appropriate AEDs.[3]

Among other neurological diseases migraine is most important and frequent type of headache in children. Prevalence of migraine among school-aged children between 7 and 15 years of age is 4% and ranges from 8% to 23% in adolescents.[2] Migraine in adolescents also has been associated with disability as evidenced by missed school days[4,5] and a negative impact on quality of life.[6] Cerebral palsy has prevalence of 4/1000 live birth. Developmental delay occurs in 10% of children due to various underlying conditions.[7] Behavior related disorders include BHS, aggression, ADHD and conduct disorder.[2] BHS occurs in 4-13% of psychosomatic diseases and 27% of otherwise normal children.[7] PDDs include autistic disorders, Asperger disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, and Rett’s disorder.[2]

Pharmacotherapy is an important aspect for management of neurological diseases. Because of the limited number of clinical trials performed in children many of the drugs given to children may be off-label or unlicensed. Off-label use includes the practice of prescribing pharmaceuticals for an unapproved indication or in an unapproved age group, unapproved dose or unapproved form of administration.[8] Unlicensed use includes modifications to licensed drugs (such as dispensing a drug in a different form, for example, crushing tablets to prepare a suspension), drugs that are licensed, but the particular formulation is manufactured under a special license (such as when an adult preparation is not suitable for use in children and a smaller dose must be formulated), new drugs available under a special manufacturing license.[9]

As limited studies have been carried in pediatric neurological disorders, it is important to study the drugs prescribed for the management of neurological diseases in children. Drug utilization research as defined by World Health Organization (WHO) as “the marketing, distribution, prescription, and use of drugs in society, with special emphasis on the resulting medical, social, and economic consequences. The ultimate goal of drug utilization research must be to assess whether drug therapy is rational or not.”[10]

Hence, a study was planned with the objectives of evaluating drug utilization pattern in pediatric neurology outpatient department, to identify off-label and unlicensed drug use and to analyze the prescriptions for potential drug-drug interactions (pDDI).

Methods

This was a prospective cross-sectional study carried out from October 2012 to December 2012. Study began after approval of Institutional Review Board. All the patients (0–16 years) attending outpatient department of pediatric neurology were enrolled in the study after obtaining written consent from a parent or legal guardian of the patient after explaining the aim of the study.

Demographic data and clinical data, as well as complete prescription, were recorded on the case record form. Data was analyzed for morbidity pattern, drug use pattern and WHO core prescribing indicators.[11] Off-label and unlicensed drug use was identified using the British National Formulary for Children (BNFC) 2011-2012[12] and National Formulary of India (NFI) 2011.[13] Adherence to National Institute of Health Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline for management of epilepsy was noted.[14] pDDI was analyzed using the online Medscape drug interaction checker,[15] and standard textbooks of pharmacology and medicine. Data was analyzed by statistical software SPSS 21.0 version (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences from IBM).

Results

A total of 140 prescriptions were collected. The male, female ratio was 2:1. Out of 140 patients, 103 (73.57%) cases were diagnosed with seizures. Partial seizure being most common (52.42%) followed by generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS) 32%, absence seizure 6.79%, unclassified type epilepsy 4.85%, infantile spasms 2.91% and myoclonic seizure 0.97% [Table 1].

| Demographic | n=140(%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 93 (66.42) | |

| Female | 47 (33.57) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 0-5 | 67 (47.85) | |

| 6-10 | 44 (31.42) | |

| 11-15 | 29 (20.71) | |

| Provisional diagnosis | ||

| Epilepsy | 103 | (73.57) |

| Behavior related disorder - breath holding spell | 09 | (7.85) |

| Other behavior related disorders | 02 | (1.42) |

| Migraine | 07 (5) | |

| Pervasive developmental disorders | 05 | (3.57) |

| Others | 14 (10) | |

Table 1: Demographic data and clinical characteristics of patients in pediatric neurology department

Majority of patients were of age group 0–5 years (47.85%) with high male preponderance. In this age group most common diagnosis was epilepsy in 49 (73.13%) cases which included 17 (34.69%) cases of partial seizures, 17 (34.69%) cases of GTCS, 4 (8.16%) cases of absence seizures, 3 (6.12%) cases of infantile spasm, 1 (2.04%) case of myoclonic seizures, and 7 (14.28%) cases of unclassified seizures. The next common clinical condition diagnosed in 0–5 years age group was behavior related disorder in the form of BHS in 9 (7.85%) cases [Table 2].

| Demographic | n=67(%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 0-5 | 67(47.85%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 43 (64.18) |

| Female | 24 (35.82) |

| Provisional diagnosis | |

| Epilepsy | 49 (73.13) |

| Behavior related disorder - breath holding spell | 09 (7.85) |

| Pervasive developmental disorders | 02 (2.99) |

| Others | 07 (10.44) |

Table 2: Demographic data and clinical characteristics of patients in pediatric neurology department in 0-5 years of age group

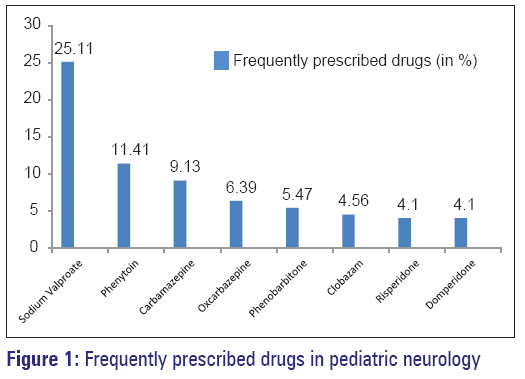

As shown in Figure 1, most commonly prescribed drugs in pediatric neurology outpatient department were sodium valproate (25.11%), phenytoin (11.41%), and carbamazepine (9.13%).

Utilization pattern of antiepileptic drugs

About 80% of cases of epilepsy were on monotherapy while the rest were on polytherapy. Majority of AEDs prescribed were conventional (84.25%). Among newer AEDs, oxcarbazepine (9.58%) was the most commonly prescribed drug followed by vigabatrin (3.42%) [Table 3].

| Conventional | Monotherapy | Polytherapy |

|---|---|---|

| (n=82) (%) | (n=21) (%) | |

| Sodium valproate | 36 (35) | 19 (18.44) |

| Carbamazepine | 12 (11.7) | 08 (7.76) |

| Benzodiazepines (clobazam, lorazepam) | 00 | 11 (10.7) |

| Phenytoin | 09 (8.7) | 16 (15.5) |

| Phenobarbitone | 09 (8.7) | 03 (2.9) |

| Newer drugs | ||

| Oxcarbazepine | 11 (10.7) | 03 (2.9) |

| Vigabatrin | 05 (4.85) | 00 |

| Topiramate | 00 | 00 |

| Levetiracetam | 00 | 03 (2.9) |

AED: Antiepileptic drug

Table 3: Pattern of AEDs use (n=103)

In children belonging to 0-5 years of age group, 73.46% cases of epilepsy were on monotherapy and more than 80% of cases were prescribed conventional AEDs. In this age group most commonly prescribed newer AED was vigabatrin [Table 4].

| Conventional | Monotherapy | Polytherapy |

|---|---|---|

| (n=36) (%) | (n=13) (%) | |

| Sodium valproate | 15 (30.61) | 12 (24.48) |

| Carbamazepine | 06 (12.24) | 01 (2.04) |

| Clobazam | 00 | 06 (12.24) |

| Phenytoin | 04 (8.16) | 03 (6.12) |

| Phenobarbitone | 06 (12.24) | 01 (2.04) |

| Newer drugs | ||

| Vigabatrin | 05 (4.85) | 00 |

| Oxcarbazepine | 00 | 02 (4.08) |

| Levetiracetam | 00 | 01 (2.04) |

| Topiramate | 00 | 00 |

AED: Antiepileptic drug

Table 4: Pattern of AEDs use (n=49) in 0-5 years of age group

Sodium valproate followed by carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine were most commonly prescribed AEDs as monotherapy. In 0-5 years age group too, sodium valproate was most commonly prescribed, followed by carbamazepine, phenytoin and phenobarbitone. In polytherapy, sodium valproate was commonly prescribed drug along with clobazam, phenytoin and oxcarbazepine. More than 80% AEDs were prescribed as per NICE guideline, January 2012 for management of epilepsy.

Drug use in other neurological diseases

Breath holding spells was the other common condition among pediatric age group, and all cases belonged to age group of 0-5 years. These cases were treated with oral iron preparations. Migraine was diagnosed in seven cases (all cases >5 years of age), and acute cases were treated with paracetamol and ibuprofen with the appropriate dose for age while chronic cases were prescribed topiramate. Developmental delay was the most common comorbid condition associated with epilepsy (in 26 cases), and it was also associated with behavior related diseases. To enhance cognition nootropics (piracetam and pyritinol) was prescribed in seven cases. Risperidone was prescribed for behavior related disorders, ADHD and for PDDs.

World Health Organization core prescribing indicators

Average number of drugs per prescription was 1.56. Percentage of drugs prescribed by generic name was 8.2%. Percentage of drugs prescribed from essential drug list of India 2011[16] was 70.31% and from WHO drugs list of children 2011[17] was 63.47%. Antibiotics and injectable drugs were not prescribed.

Off-label/unlicensed drug use in children with neurological disorders

A total of seven cases were found with off-label drug use and five cases with unlicensed drug use, as per BNFC 2011-2012 and NFI 2011 [Table 5].

| Drug | Indication | Number of cases (12) | Off-label/unlicensed category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxcarbazepine | GTCS - 600 mg BD | 3 | Inappropriate dose |

| Sertraline | GTCS | 1 | Not indicated in this condition |

| Child was 3-year-old | |||

| Not indicated in the child<6 years | |||

| Sertraline | Undiagnosed nausea, vomiting | 1 | Not indicated in this condition |

| Lorazepam | Partial seizure | 1 | Not indicated in this condition |

| Alprazoalm | Behavior related disorders | 1 | Not indicated in this condition |

| Not recommended as per NFI | |||

| Topiramate | Migraine prophylaxis | 3 | Not licensed in children for this condition |

| Risperidone | Behavior related disease | 2 | Not licensed in children<5 years |

GTCS: Generalized tonic-clonic seizure, NFI: National Formulary of India, BD: Twice daily

Table 5: Off-label and unlicensed drug use in children with neurological disorders (n=140)

Potential for drug-drug interactions

A total of 82 pDDI were recorded in 26 patients (18.57%), out of which 68 (82.92%) were pharmacokinetic, 9 (10.97%) were pharmacodynamic and 5 (6.09%) interactions were with an unknown mechanism. A few of such cases are shown in [Table 6].

| Drug combinations | Pharmacokinetic | Pharmacodynamic | Unknown | Total number of |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| interactions | interactions | mechanism | such cases (11) | |

| Phenytoin+sodium valproate | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Phenytoin+carbamazepine | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Phenytoin+phenobarbitone | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Phenytoin+sodium valproate+carbamazepine | 8 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Phenytoin+carbamazepine+risperidone+clonazepam | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Table 6: Potential drug-drug interactions in pediatric neurology

Discussion

This drug use study was carried out in the pediatric neurology outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital. Majority of cases were of epilepsy showing high male preponderance, partial seizure (48.64%) being most common followed by -GTCS (35%). The results are comparable to previous studies from Malaysia and Bangalore.[3,18] In our study, majority of patients were of age group <5 years with high-male preponderance and among them the most common diagnosis was epilepsy. These results are comparable to the previous study from Bangalore.[18] Drug therapy is the mainstay of treatment of various types of epilepsy. In our study, sodium valproate was the most commonly prescribed drug which was also reported by Hasan et al.[3] Recent study from UK reported valproate (22%) followed by carbamazepine (21.3%) as most commonly used AEDs.[19] The current NICE guidelines advise either carbamazepine (focal seizures) or sodium valproate (focal or generalized seizures) as the first line of therapy for epilepsy.[13] In our study, sodium valproate was commonly prescribed AED either as monotherapy or polytherapy in 0-5 years of age group. Although, sodium valproate is an effective AED it stands the risk of fatal hepatic failure especially in children under 3 years of age.[12] However, liver function tests of children <3 years of age who were prescribed sodium valproate were monitored or not were unknown due to cross-sectional nature of the study. In our study, over 80% AEDs were prescribed as per NICE guidelines. In the case of no seizure control with one drug, alternative monotherapy should be tried before considering polytherapy.[14] In our study, monotherapy was used in about 80% of children with seizure disorders. This is desirable because using one-drug controls seizure in most patients with fewer possible side effects.[2,14] Monotherapy is preferred to polytherapy because of lower cost associated with medication, reduced potential for adverse reactions, undesirable drug interactions and improved medication compliance with a more simplified drug administration schedule.[18] This carries greater significance as our study population is children and adolescents.

The newer AEDs cannot be recommended as first-line drugs because of limited clinical experience and cost factor wherein the use of these drugs should be reserved for epileptics not responding to conventional drugs. In our study, oxcarbazepine was the most commonly prescribed newer AED in contrast to lamotrigine being commonly prescribed newer AED in study by Maity and Gangadhar.[18]

In children <5 years most commonly prescribed newer AED was vigabatrin for infantile spasm. Vigabatrin was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 2009 for use as monotherapy in the treatment of infantile spasms in patients aged 1 month to 2 years when the benefits of treatment outweigh the risks.[20] However, mainstay of treatment for infantile spasms is adrenocorticotropic hormone according to NICE guidelines.[14]

Polytherapy in refractory epilepsy can produce additive, antagonistic or synergistic efficacy and toxicity.[21] AEDs with similar mechanisms of action would be expected to produce additive efficacy while AEDs with differing mechanisms of action would be expected to be synergistic.[22] However, AEDs are prone to cause several drug-drug interactions (DDIs) when prescribed concomitantly. The main pharmacokinetic interactions to consider are at the level of protein binding resulting in drug displacement interactions. Interactions also are expected at the level of metabolism involving cytochrome P450. Co-administration of the enzyme-inducing AEDs (i.e. phenobarbital, phenytoin, or carbamazepine) with inducible AEDs (such as lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, tiagabine, topiramate, or zonisamide) hastens the metabolism of the latter, reducing their concentrations and efficacy.[22] Valproate primarily inhibits the metabolism of drugs that are substrates for CYP2C9, including phenytoin and phenobarbitone. A high proportion of valproate is bound to albumin and in the clinical setting it displaces phenytoin and other drugs from albumin. Concentration of phenobarbitone in plasma may be elevated by as much as 40% during concurrent administration of valproate. The outcome of the interaction between phenytoin and phenobarbitone is variable.[23] In our study, most commonly used dual drug combination is sodium valproate and clobazam which do not lead to any DDIs. However, in our study phenytoin with valproate, phenytoin and valproate with carbamazepine were also frequently prescribed in combination which could lead to various DDIs.

Breath holding spells, behavior related disorder are apparently frightening events occurring in otherwise healthy children.[2] BHS generally abate by 5 years of age[2] and in our study, all cases of BHS were from 0 to 5 years of age. A study from Pakistan to determine the usefulness of piracetam as prophylactic treatment for severe BHS also had included children from 0 to 5 years of age.[24] Generally, no medical treatment is recommended, and parental reassurance is believed to be enough, however, severe BHS can be very stressful for the parents and a pharmacological agent may be desired in some of these children.[24] A Cochrane review of trials assessing the effect of iron supplementation on the frequency and severity of breath-holding attacks in children concluded that iron supplementation significantly reduced the frequency of breath-holding attacks in children.[25] In a study of parental attitude of mothers, iron deficiency anemia, and BHS by Hüdaoglu et al. suggests that iron deficiency anemia rather than behavioral or psychosocial problems of mothers plays a role in the development of BHS.[26] In our study, all cases of BHS were treated with oral iron preparations.

Migraine is a frequent type of headache among children. Management of an acute attack should include the use of analgesics and antiemetics.[2] Some studies also suggest that triptans can be a useful therapeutic option for severe episodes of acute migraine unresponsive to analgesics in children and adolescents.[27,28] However, use of triptans for children is unlicensed as per BNFC 2011–2012 for children.[12] In our study, prophylactic topiramate was prescribed in three cases of chronic migraine. A study by Winner et al. suggests that topiramate may be an effective migraine preventive therapy in children.[29] Another study by Lakshmi et al. showed that decrease in school absenteeism was significant with topiramate compared with placebo.[30] Propranolol and flunarizine are the only two drugs subjected to controlled studies to test efficacy and tolerability of these drugs in reducing severity of childhood migraine.[2] Moreover, topiramate should not be used in children <12 years for migraine prophylaxis.[12]

Autism and related PDDs are characterized by impairments in social interaction and communication, restricted interests, and repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior.[2] PDDs affected children frequently present with hyperactivity, tantrums, physical aggression, self-injurious behavior, stereotypies and anxiety symptoms. Intensive behavior therapy, parent education and pharmacotherapy with atypical antipsychotics are effective for symptomatic relief in PDDs.[2,31] In our study, such cases were treated with risperidone. In some countries, including the USA, risperidone is licensed for the treatment of irritability associated with autistic disorder in children and adolescents aged 5-16 years.[32] The BNFC also suggests that risperidone may be used, under specialist supervision, in children over 5 years of age for the short-term treatment of severe aggression in autism.[12] In our study, two cases of behavior related disorder (<5 years) were prescribed risperidone which was unlicensed as per BNF.[12] Risperidone may be of some benefit for symptoms such as hyperactivity, irritability, repetition, and social withdrawal. However, this must be weighed against the risk of adverse effects, notably weight gain and hyperprolactinaemia which could lead to hypogonadism and deleterious effects on adolescent bones.[32]

World Health Organization core prescribing indicators reflect the overall prescribing pattern and rationality at a particular health care facility. We found that over 90% drugs were prescribed by brand names. This practice is likely to increase the cost of therapy.

We have reported drug utilization pattern in pediatric neurology department which gives insight into current pharmacotherapy practices in childhood neurological disorders. It also highlights off-label/unlicensed drug use in children and also the possibilities of pDDIs. To our knowledge, such study has not been reported in India. The limitations are data from an outpatient department with a small sample size. Hence, the findings cannot be generalized. Moreover, patients enrolled in the study could not be followed-up for the occurrence of adverse drug reactions or occurrence of actual DDIs.

Conclusion

This study may help in evaluating existing drug use pattern and rationality of prescription. In pediatric neurology, partial seizure was the commonest neurological disease and sodium valproate the most commonly prescribed drug. Most of the AEDs were prescribed as per NICE guidelines for the management of epilepsies. Polytherapy for management of epilepsy increases pDDI. Only few prescriptions contained off-label/unlicensed drugs. Further such studies with large sample size in pediatric neurology would guide clinicians toward rational drug prescribing.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Dr. Pankaj R. Patel, Dean of Smt. NHL Municipal Medical College, Dr. Darshana Naik, Dr. Nitish Vora, and Dr. Siddharth Shah neurology consultants for their valuable support.

References

- Raina SK, Razdan S, Nanda R. Prevalence of neurological disorders in children less than 10 years of age in RS Pura town of Jammu and Kashmir. J Pediatr Neurosci 2011;6:103-5.

- Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF. Nelson Text Book of Pediatrics. 18th ed., Vols. I and II, Chs. 28, 29, 593, and 595. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2007. p. 131-7, 2457, 2477-81. [Indian Print 2008].

- Hasan SS, Bahari MB, Babar ZU, Ganesan V. Antiepileptic drug utilisation and seizure outcome among paediatric patients in a Malaysian public hospital. Singapore Med J 2010;51:21-7.

- Abu-Arefeh I, Russell G. Prevalence of headache and migraine in schoolchildren. BMJ 1994;309:765-9.

- Stang PE, Osterhaus JT. Impact of migraine in the United States: Data from the national health interview survey. Headache 1993;33:29-35.

- Powers SW, Patton SR, Hommel KA, Hershey AD. Quality of life in childhood migraines: Clinical impact and comparison to other chronic illnesses. Pediatrics 2003;112:e1-5.

- Gupte S. The Short Textbook of Pediatrics. 11th ed., Chs. 5, 6 and 23. India JP Press; New Delhi; 2009. p. 46-8, 53-5, 413.

- Howland RH. Off-label medication use. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2012;50:11-3.

- Turner S, Longworth A, Nunn AJ, Choonara I. Unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards: Prospective study. BMJ 1998;316:343-5.

- Availablefrom:http://www.whocc.no/filearchive/publications/ drug_utilization_research.pdf. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 20].

- Availablefrom:http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/ Js2289e/3.2.html. [Chapter 2, Group 1]. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 20].

- British National Formulary for Children (BNFC) 2011–2012. Available from: http://www.sbp.com.br/pdfs/British_National_Formulary_for_ Children_2011-2012.pdf [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 20].

- National Formulary of India (NFI) 2011. Available from: http://mohfw. nic.in/showfile.php?lid=1419 [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 20].

- National Institute for Health Clinical Excellence (NICE). Clinical Guideline 137. The epilepsies:The diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care-full guideline, January 2012. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg20/ resources/guidance-the-epilepsies-the-diagnosis-and-management-ofthe- epilepsies-in-adults-and-children-in-primary-and-secondary-carepdf [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 20].

- Medscape drug interaction checker. Available from: http://reference. medscape.com/drug-interaction checker. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 20].

- Essential drug list of India 2011. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/ documents/s18693en/s18693en.pdf [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 20].

- WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children 3rd list (March 2011).http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2011/a95054_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 20].

- Maity N, Gangadhar N. Trends in utilization of antiepileptic drugs among pediatric patients in a tertiary care hospital. Curr Neurobiol 2011;2:117-23.

- Moran NF, Poole K, Bell G, Solomon J, Kendall S, McCarthy M, et al. Epilepsy in the United Kingdom: Seizure frequency and severity, anti-epileptic drug utilization and impact on life in 1652 people with epilepsy. Seizure 2004;13:425-33.

- Pesaturo KA, Spooner LM, Belliveau P. Vigabatrin for infantile spasms. Pharmacotherapy 2011;31:298-311.

- Czuczwar SJ, Borowicz KK. Polytherapy in epilepsy: The experimental evidence. Epilepsy Res 2002;52:15-23.

- St Louis EK. Truly "rational" polytherapy: Maximizing efficacy and minimizing drug interactions, drug load, and adverse effects. Curr Neuropharmacol 2009;7:96-105.

- Brunton LL. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. McGraw-Hill, New York. 2010: p. 596-8.

- Azam M, Bhatti N, Shahab N. Piracetam in severe breath holding spells. Int J Psychiatry Med 2008;38:195-201.

- Zehetner AA, Orr N, Buckmaster A, Williams K, Wheeler DM. Iron supplementation for breath-holding attacks in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; Issue 5, Page 1.

- Hüdaoglu O, Dirik E, Yis U, Kurul S. Parental attitude of mothers, iron deficiency anemia, and breath-holding spells. Pediatr Neurol 2006;35:18-20.

- Bonfert M, Straube A, Schroeder AS, Reilich P, Ebinger F, Heinen F. Primary headache in children and adolescents: Update on pharmacotherapy of migraine and tension-type headache. Neuropediatrics 2013;44:3-19.

- Toldo I, De Carlo D, Bolzonella B, Sartori S, Battistella PA. The pharmacological treatment of migraine in children and adolescents: An overview. Expert Rev Neurother 2012;12:1133-42.

- Winner P, Pearlman EM, Linder SL, Jordan DM, Fisher AC, Hulihan J, et al. Topiramate for migraine prevention in children: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache 2005;45:1304-12.

- Lakshmi CV, Singhi P, Malhi P, Ray M. Topiramate in the prophylaxis of pediatric migraine: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Child Neurol 2007;22:829-35.

- Politte LC, McDougle CJ. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;231:1023-36.

- Sweetman SC. Martindale’s The Complete Drug Reference. 36th edition,London Pharmaceutical Press. Pharmaceutical Press; 2009. p. 1026.